3. Changing the narrative on democracy

It's time for changemakers to challenge the status quo, engage citizens in participatory democracy, and build a more hopeful future.

Global narratives are shifting before our eyes. The question is: can civil society push back?

Since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the U.S. has positioned itself as a champion of Ukrainian sovereignty, and its actions reflected a clear narrative of standing for human rights and democracy. Last week, we saw that change dramatically before our eyes, as the U.S. turned its back on Ukraine and reinforced dangerous narratives about the war—and the value of democracy itself—propagated by Russia.

Over the last years (and even decades), humanitarian aid was something the world proudly supported, and now, we’re watching that consensus unravel. The U.S. foreign aid freeze and wavering commitments from other global actors show us just how quickly values can be rewritten.

But there’s good news, we promise. Narratives don’t just shift on their own: people shape them. And civil society has the power to push back. We’ve seen it happen before and we can do it again.

This month, REWIRE Democracy is exploring how civil society leaders and changemakers can actively shift harmful narratives to move from fear to hope, problems to solutions, and exclusion to participation.

In this issue, you’ll find:

An introduction to narrative change: what it is, why it matters, and how it works

A deep dive into how we can (and why we should) reframe democracy as something citizens co-create, not just consume

Resources from our community to help you strengthen your messaging around harmful narratives

Let’s dive in. ⬇️

💛💙 REWIRE Democracy stands with Ukraine 💙💛

What is narrative change?

Narrative change is the process of reshaping the stories that define how people understand the world.

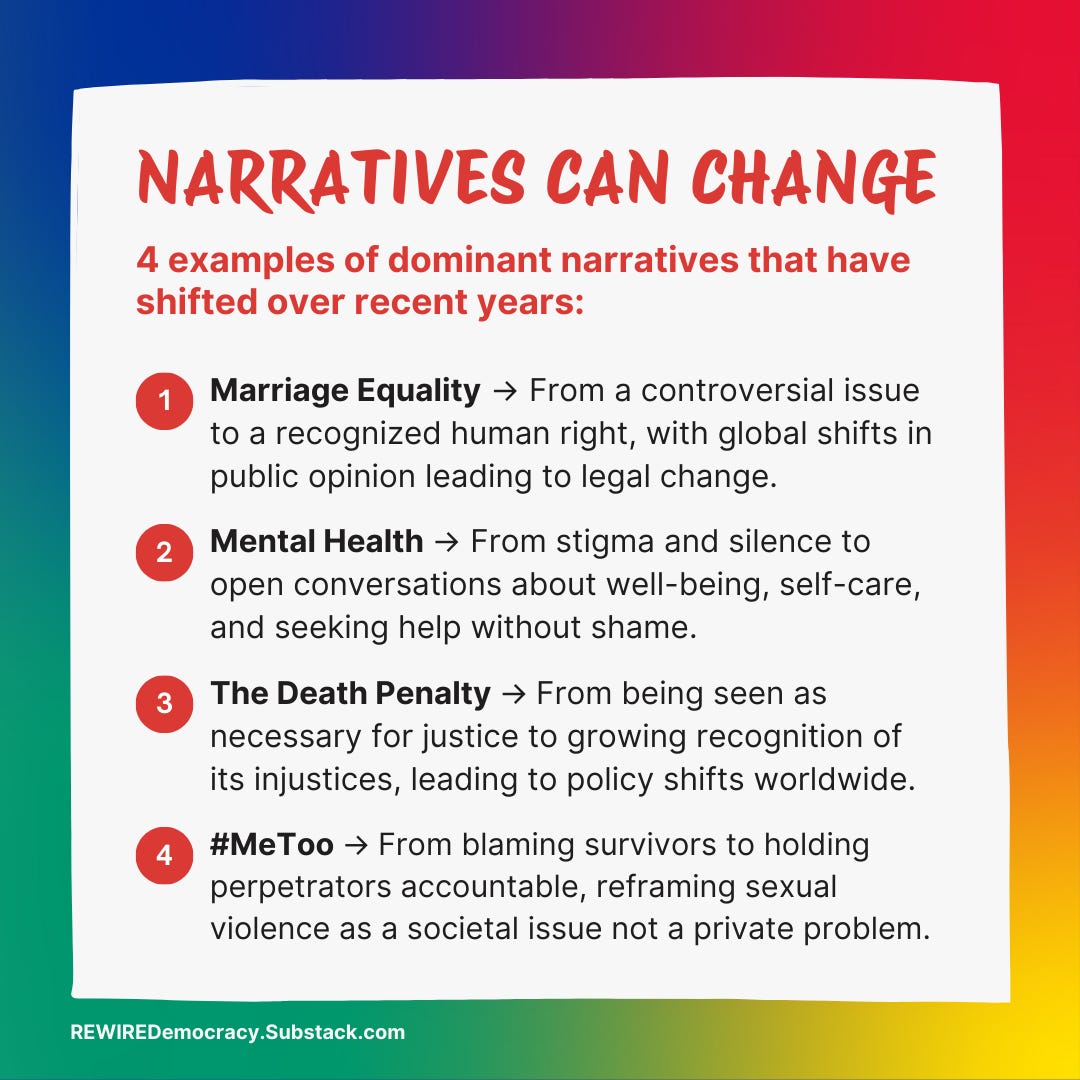

And history shows that it works. For example, public support toward same-sex marriage in the US grew to 71% in 2023 from just 27% in 1996 (Statista), thanks to the relentless work of activists. From the #MeToo movement to widespread attitudes surrounding the death penalty, narrative shifts have historically been pivotal in advancing social justice causes.

These shifts didn’t happen by accident. They are the result of intentional, strategic efforts to challenge dominant stories and introduce new ones that inspire action and change.

What we can all do, right now, is pause and reflect strategically on the narratives we’re reinforcing in our messaging. Are we upholding outdated systems we actually want to replace? Are we inadvertently feeding narratives of fear and division instead of hope and possibility?

We have the power to challenge dominant narratives that reinforce injustice and replace them with narratives that inspire action, hope, and progress.

If we want to shift the future, we need to be intentional about the stories we tell. Because the narratives we create today shape the world we live in tomorrow.

📝 The Learning Curve

It’s time to change the narrative around ‘democracy’

By Zsofia Banuta, Co-founder of Unhack Democracy

We are not being bold enough in civil society. There, I said it.

For too long, we’ve defended status quo institutions, upheld broken systems, and filled in the gaps where governments have failed. But are these institutions we’re upholding actually working? Are they truly serving the people they claim to? Or are we just preserving a system that no longer meets the needs of society?

We are at a tipping point. If we don’t create something new, we risk losing democracy altogether. And if we truly want to transform democracy, we need to stop patching up a system in decline and start building something new.

The ‘consumer’ model of democracy is collapsing, what comes next?

As Jon Alexander posits, democracy is framed through a ‘consumer’ narrative: politicians act as service providers, and citizens are passive consumers choosing from a fixed set of options.

This model is outdated, and people are clearly losing faith in it. Across Europe and beyond, we see growing frustration with the system, leading many to turn toward authoritarian leaders who offer the illusion of certainty and control.

But the real problem isn’t just the politicians. It’s the way we’ve structured participation in democracy itself. Top-down governance, rigid political party systems, and even the bureaucratic donor model in civil society all reinforce a passive model of democracy that fails to engage people in shaping decisions that affect their lives.

The traditional, top-down model is eroding, yet much of civil society remains focused on stabilizing and defending it. Meanwhile, authoritarian movements are rising, offering false certainty. The real opportunity lies in investing in new, participatory models of democracy that actively engage citizens in shaping their future. If we want democracy to survive, we must stop merely protecting our idea of democracy (the status quo), and start redesigning it.

Reframing democracy as collective action

We need a new democratic narrative: one that positions citizens as active participants, not passive consumers, a concept that is fleshed out in the book Citizens by Jon Alexander, along with inspirational examples of this idea in practice from Mexico to Taiwan.

Democracy should not be something that happens to people, it should be something they actively shape; a system where power isn’t hoarded at the top but shared among the people who live with its consequences.

So what does civil society do now?

Change starts with reframing the story. We need to:

Rethink our role. Civil society can’t just be about defending democracy, it must be about redesigning it.

Push for real participation, don’t just send out surveys. Donors, governments, and institutions must co-create decisions with the people they serve, not impose solutions from above.

Break the ‘passive citizen’ model. Move beyond ‘awareness-raising’ to hands-on engagement, where people actively shape decisions.

Build new alliances. Connect with grassroots movements, innovators, and thought leaders already working to shift power back to the people.

Tell a new story about democracy. If we want people to engage in democracy, we need to change the way we talk about it: from something that happens to them, to something they own, shape, and build together.

The consumer democracy model has been dominant for 80+ years, but we are at a massive breaking point in history. Will civil society continue to uphold a failing system, or will we be bold enough to build something new?

💬 Do you have any great examples from your community that puts citizens at the heart of decision making? Let us know in the comments!

🔗 Resource Round-Up

Dive into these resources from our community to learn more about narrative change

🎨 Reframing narratives through visual storytelling: Fine Acts and TheGreats.co - Want to challenge the dominant (visual) narratives around the topics you work on? You can use global creative studio Fine Acts’s library of thousands of free illustrations from great artists that showcase a more positive and hope-based version of the future at TheGreats.co!

💡 Hope-Based Communication: Subscribe to the Hope-based Substack newsletter and How to Hope in Dark Times TED Talk - Thomas Coombes, founder of Hope-Based Communication and the REWIRE Incubator, offers a strategy for shifting narratives away from fear and crisis and toward solutions, optimism, and collective action.

💙💛 Upcoming webinar on 6th March: Civil Society & Security in Ukraine - Civil society is often seen as a force for democracy and human rights, but Ukraine has shown that in times of war, it can also become a pillar of security. What lessons can other civil society leaders learn from Ukraine’s experience? Join this insightful discussion on with Oleh Rybachuk (Former Deputy PM for European Integration & Head of the Centre of United Actions) and Olha Aivazovska (Chair of OPORA & Co-founder of the International Centre for Ukrainian Victory) on March 6, 2025, at 18:00 (Kyiv) / 17:00 (Budapest) / 16:00 (London). Online webinar, open to the public. See you there!

Ready to change some narratives? ⚡️

Remember: dominant narratives aren’t inevitable, they’re constructed by people. And if we want to strengthen democracy, we will need to challenge and reframe the stories that shape public opinion.

💬 What’s one dominant narrative in your line of work that we can challenge? Share your thoughts with us in the comments below!

I truly appreciate your essay. And yet, I find myself stumbling again and again over the idea that narratives have truly shifted. On the surface, yes—it might look that way.

I live in Germany, a relatively stable country where many human rights have advanced over the last 30 years. As a non-binary lesbian, I now have rights I didn’t have growing up in the ’70s and ’80s—years marked by ostracism because of my gender nonconformity and, later, because I was openly homosexual.

You’d think that general acceptance has truly evolved alongside these legal changes—queer rights, trans rights, anti-discrimination laws. And it does look like that, again, on the surface. But my lived experience tells another story.

Yes, there are people who are open-minded, tolerant, welcoming—and I honor them. But I also believe such people have always existed, shaped by how they were raised or how they’ve grown. Their kindness is not a product of new laws. And that leads me to ask:

If narratives have truly shifted, why do we still need so many laws and provisions just to be safe?

Rights once granted—and seemingly secure for future generations—can be taken away in an instant. Just look at the U.S., where today, being trans can lead to a dishonorable military discharge. That’s not just a policy reversal; it’s a dangerous narrative in motion. And it’s only the beginning.

Here in Germany, my body still doesn’t feel safe. There’s no immediate, tangible threat—but the unease remains. Why? Because I’ve been ostracized simply for not staying invisible. I speak openly about being non-binary, lesbian, neurodivergent—and that makes people uncomfortable. Because I’m different. Because they fear the other.

Because I refuse to vanish, I must remain vigilant. The next passerby might hurl slurs—or worse, give the glance, that quiet weapon of superiority. You might say that’s illegal—and yes, it is. But it still happened to me last year. And not from a stranger I expected it from, but from someone I once believed to be liberal.

I’ve felt it over and over: whispered conversations that stop when I arrive. Invitations that dry up when I no longer initiate. The subtle erasures. The passive exclusion. And it’s not because I didn’t try to connect.

But if connection requires my denial, then it is not connection at all.

This is still reality—especially in rural Germany. Subcultures within subcultures exist for a reason: because it’s damn hard to live when you’re socially isolated.